This tutorial aims to explain what yaw is, why it occurs, how it occurs, how to detect it, and how it affects the appearance of a diamond. I will also try to clear up the confusion regarding this topic in relation to the terms yaw, twist, distortion, and azimuth shift.

What is Facet Yaw?

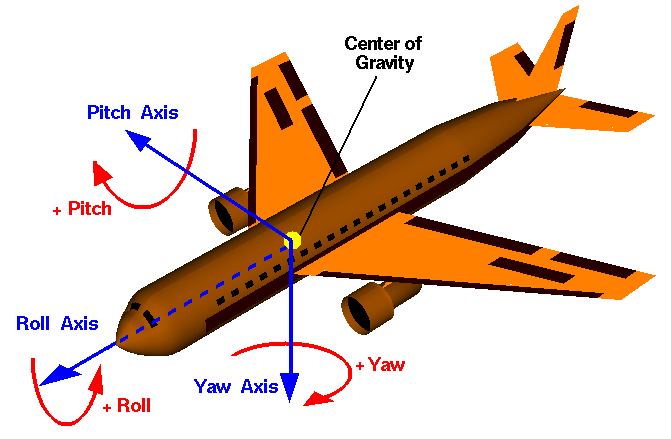

Facet yaw, a term coined by Brian Gavin, is a type of facet distortion that can occur either through poor cutting or tricky cutting. The technique of yawing a facet can be used to tweak the diamond’s proportions while maintaining the lab-graded symmetry grade. Like painting of the girdle, yawing is therefore potentially a swindling strategy. In the industry, the term ‘cheated’ is sometimes used referring to the facet where swindling strategies was used. Yaw is a confusing term primarily because it is difficult to visualise; and secondly because of its naming. In engineering, yaw refers to a rotation in the corresponding z-axis. Those of us who are familiar with airplanes or gyroscopes will know that the other axes are named pitch (y-axis) and roll (x-axis).

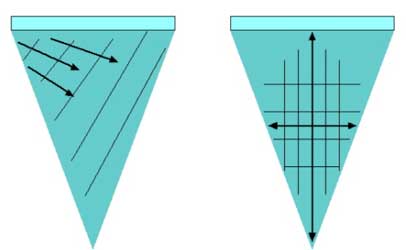

This marks the most important difference between yaw and indexing, because indexing is still cutting from the north south direction. The problem cutting from the east west direction is that it causes one side of the facet to spend a bit more time in contact with the cutting wheel than the other side.

One side of the facet has more material removed from it causing the facet angle to change. At the new angle, the facets would normally not meet nicely at the girdle. The result of the cutter’s techniques to correct the facet meet-points causes what is referred to as ‘azimuth shift’. Now the azimuthual direction is also known as the ‘hoop’ or circular direction; that is the direction you would be walking if you were walking in a circle. An shift in the azimuth direction will be like moving from one position in a circle to another. The shift in the facet is accompanied by a change in slope and the cutter will try to hide this as much as he can by gradually changing the slope. The effect of this change in slope is that the end point of the facet would have moved away from the girdle. Imagine splitting up the original facet into several facets so that some of these new facets end on a point, which is on one of the other new facets, rather than extending to the girdle. This technique can be effective to hide the effect from casual observers and from digital scanners that don’t check for it. Suffice to say it takes a tremendous amount of skill in order to hide this effect because it involves yawing of at least three of the lower girdles in order to ensure that the meet-point-symmetry remains intact. I can finally bring it altogether and form the definition of yaw in diamonds. Yaw is the observable result of shifting the azimuth of the end point of a facet. It is a complication of the cutting process that leaves a defect, which in the most minor of cases can only be detected in a properly taken H&A image. The resultant effect would look like the facets have excellent meet-point-symmetry but in fact the physical and therefore optical symmetry has been compromised. A further effect of yaw is that a part of the yawed facet has to be cut further into the girdle than originally in order to hide the other meet points and this has the effect of making the girdle thinner at the yawed facet. Visually, the appearance of minor yaw is difficult to detect from a face-up position. If we take a yawed pavilion facet for example, theoretically the yawing will cause a different slope producing a slightly different light return signature. I doubt this will be noticeable though, even in an idealscope image. However, because three other lower girdles have to have their slopes varied, the lower girdle lengths will be affected the most. This could have the effect of tilting some of the hotspots, but this is not a reliable method to detect yaw, as too much effort has to go into making sure the viewing environment is level. By far the best way to detect yaw is using the hearts image. As we learned from the previous tutorial, the Vs in a hearts image indicate variation of the lower girdles and uneven Vs will indicate even the most minor effects of yaw. Also, because the hearts are formed from two different pavilion facets, any variation in the pavilion facets will cause misaligned hearts.

Yaw is probably not a concern for consumers of diamonds that are marketed as near H&A. But for those of you who are seeking an H&A, it is important for you to be aware of this defect. By choosing a diamond that has no yaw, you are essentially choosing the top 10% of all super-ideal diamonds in the world.

Camera Tilt

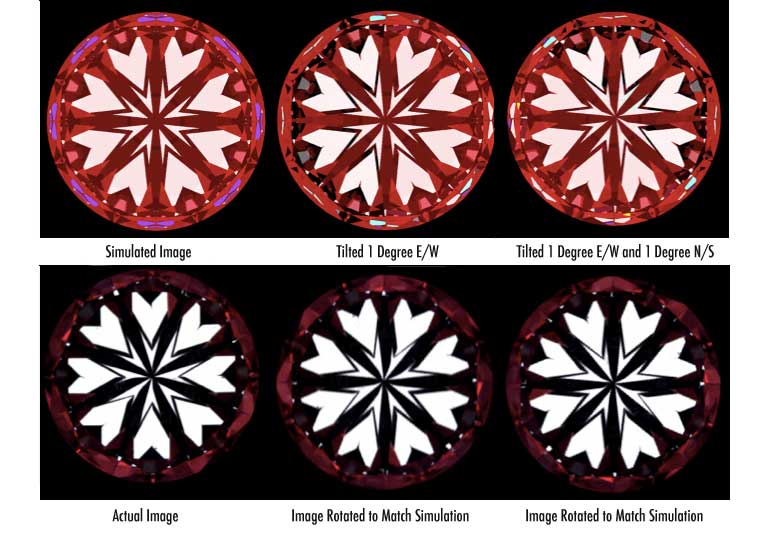

Now this brings me onto the final point, which is camera-tilt. This will not be new for those who have read my Crafted by Infinity review. The following images demonstrate what I mean by camera tilt.

You can see how just 1 degree of tilt in any part of the photography setup (camera lens, body, tripod, table, floor) can create the above illusion. This means we cannot jump to conclusions regarding yaw just because we see some distortion. Please also note that if the setup is perfectly level, the only other thing that can cause this effect is tilt of the table facet. A 1-degree tilt will be caught by the lab symmetry grade so you will know you’re dealing with camera-tilt if the diamond has an excellent symmetry grade. I have found the best way to detect any yaw that is not an illusion is to find the line of symmetry in the diamond. Once you identify the line of symmetry, you can eliminate the effects of one axis of tilt. Then you can check whether all the V’s are still a bit smaller on one side of the imaginary line of symmetry than the other to determine whether there is tilt in the other axis. Any distortion of the V’s that cannot be explained consistently by camera-tilt will have to be assumed to be yaw. Camera-tilt not only causes the illusion of yaw, but also produces what appears to be clefs in between the hearts. You can detect ‘fake’ clefs by noting how close the heart is from the V. If there are hearts in the image that show no clefs but are further from the V, yet hearts that have clefs are closer to the V, then you know that the clefs are illusions from camera-tilt.

Conclusion

We now know that yaw in diamonds is the observable effect of azimuth shift. It occurs because of complications in the cutting procedure due to irregular graining. The best way to detect it is to look at a hearts image and look for distortion of the Vs and misalignment of the hearts. However, it is important to bear in mind the effects of camera-tilt. The presence of minor yaw does not affect the face-up appearance of diamonds that much and should not be a main consideration for those seeking diamonds that are marketed as near-H&A. But for those seeking the best-of-the-best in terms of the optical symmetry that you get with a true H&A diamond, then you should look for a diamond without the presence of yaw. If you are looking for a true H&A diamond and are struggling with the photographs you see online, then please feel free to send me an email and I will do my best and try to help you out.