The upper girdle facets surround the edges of the diamond. I mentioned in the last tutorial that the star length affects the upper girdle angles, but this is only half the story. This tutorial will introduce to you the effects of upper girdle indexing, commonly referred to as painting and digging.

Before I begin, I want to credit Good Old Gold. All the images in this tutorial are copyright Good Old Gold and they have kindly allowed me to reproduce the images in this article. I would like to thank Jonathan Weingarten a.k.a. ‘Rhino’ at Good Old Gold, who has done the research and figured out some of the critical numbers for us.

Some thoughts on the upper girdle facets

Now the upper girdle facets are the only facets that are not mentioned on a diamond grading certificate. I’ve tried very hard to try to find out why this is but I haven’t found any solid information. I can only give some of my own opinions on this matter.

The most obvious to me is that the labs have never reported the upper girdle angles before due to it being considered the facet that affects the diamond’s appearance the least. However, for years, diamond cutters have been using techniques known as upper girdle indexing to manipulate the appearance of the diamond as well as to retain weight. At some point, these techniques were probably highly guarded trade secrets.

These days, the major labs are well aware of these techniques. Most agree that the techniques used to retain weight are detrimental to the appearance of the diamond. Although the labs will now consider the upper girdles in their cut grading assessment, they still do not report detailed information regarding the upper girdles.

There are many reasons for this that I can only speculate into, such as in order to save costs, reduce the time it takes to do a report, prevent confusing consumers, and to appease others in the diamond trade. Regardless of the reasons, I feel that the upper girdles are actually one of the most important facets in a diamond for a diamond prosumer. Why? Because most of you will end up buying a diamond with a CA/PA within the Tolkowsky Ideal Cut range, with 75-80% lower girdles, and with 50-55% stars. And even though my entire site is about finding what you subjectively prefer, many of you will settle on some of the more popular proportions.

By this point in the tutorials, hopefully you have a good idea of what your preferences are. However, you probably have no idea what these upper girdles are yet it is these facets that are going to differentiate your diamond from another diamond with similar specs.

Last time, I briefly mentioned how longer star facets mean steeper upper girdle angles. I also mentioned that with longer stars, the diamond is generally going to have less light return, and that with shorter stars there will tend to be less contrast. The reason is actually not in the stars themselves, but because of how the upper girdles are changed by the stars. It is the cutting of the upper girdles that sets the star length and not the other way around.

In my last tutorial, I said that the star facets and upper girdles work with the lower girdles in a similar way to how the crown works with the pavilion. Remember that the pavilion begins to leak around 41 degrees for crowns that are between 33-35 degrees. Now the star angles are typically in between 20 and 30 degrees and the lower girdles are around 40ish degrees and this is why light leakage is not a major concern in the stars.

But the relationship between the upper girdles and the lower girdles is different because the upper girdles range from the 30ish degrees to the 40ish degrees. This means that they can be manipulated in order to optimise for light return or to create some additional contrast at the edge of the diamond by introducing some light leakage into the upper girdles. The technique used by cutters to manipulate the upper girdle angle is known as upper girdle indexing.

Upper Girdle Indexing (Painting, Classic, and Digging)

Now we are going to get even more technical, which by this stage you should be well capable of following. First you need to understand that the girdle of a diamond is not round, rather most girdles are faceted and others are bruted. For excellent cut graded diamonds, we are really just looking at a faceted girdle. A faceted girdle is cut so that there are 4 girdle facets per upper girdle.

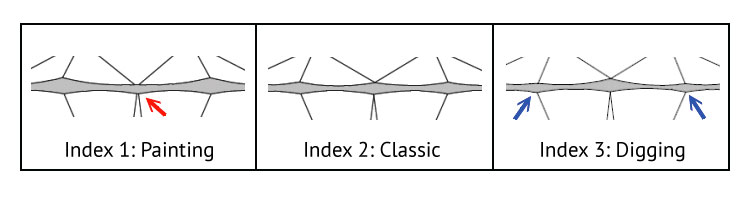

There are 3 types of upper girdle indexing (index 1, 2, and 3) and this refers to the number of the notches on the girdle facet from which the upper girdle is cut from. The notches, for lack of a better word, are the edges of each individual girdle facet. You can imagine a cutter at the cutting wheel shaping the upper girdle facets by lining up the wheel with the 1st, 2nd, or 3rd notch and then cutting the diamond from the girdle upward toward the star facet.

An important point is that you start counting the girdle facets outwards from the point where the crown and the pavilion meet the girdle (So if you go around the diamond, the upper girdle indexing will go 1, 2, 3, 3, 2, 1). It turns out that whether the cutter chooses index 1, 2, or 3, significantly affects the appearance and weight of the diamond.

Cutting the upper girdles using an index of 1 is known as crown-only painting or simply a ‘painted’ girdle, index 2 is what is called a normal index or classic girdle, and index 3 is known as digging or a ‘dug-out’ girdle.

Painting makes the upper girdles shallower. One of the reasons cutters paint the upper girdles is because they used to be able to get away with retaining some extra carat weight without changing the proportions on the certificate. These days, too much painting is noted on the GIA certificate as “brillianteering of the half facets”.

However, sometimes painting is used to improve light return. This can be achieved by crown-only painting whilst keeping the girdle thickness at the half facets the same as the way it would have been if the diamond were cut using normal indexing.

In such a case, the cutter actually loses weight rather than retain weight, which is rather counterintuitive and admittedly confusing. This is because in order to keep the crown angle the same when you paint the girdle, the crown height is reduced. The point to remember is that painting can easily push a stone in or out of those important carat bands where prices differ significantly.

Digging is the opposite of painting, and makes the upper girdles steeper. One reason a cutter will dig out the girdle is to cut away inclusions such as indented naturals that may improve the clarity grade. Another reason would be to reduce the average thickness of a girdle and make a thick girdle appear much thinner. We will see shortly how digging always negatively affects the light performance of a diamond.

In general, steeper upper girdles will tend toward light leakage. A classic girdle will have slight leakage that increases the contrast under the upper girdles themselves. The opposite is true and shallower upper girdles will tend to increase the light return and brightness under the upper girdles. A slightly-painted girdle will have a good balance between light return and contrast.

Whether a classic, slightly-painted, or painted girdle is better is really a personal choice. I’m going to try to help you understand your preferences by showing you what to expect from painting or digging.

Painted Girdles

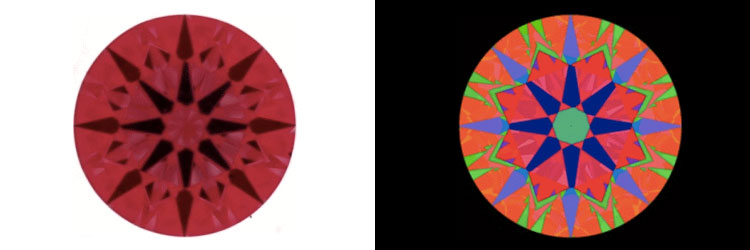

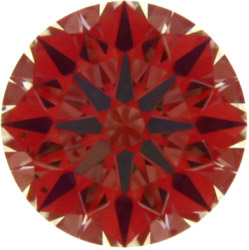

Lets first have a look at what a painted girdle looks like compared to a classic girdle.

On the left is the painted girdle. Notice how the edge of this diamond produces a more distinct dark and bright pattern. The diamond is brighter on the upper girdles near the arrows and this makes the arrows appear sharper. Diamonds of this character typically have shallower upper girdles angles between 36-39 degrees.

The diamond on the right is the one with a classic girdle. You will see that there is generally a more even contrast pattern that seems busier yet balanced. One thing I want you to really be aware of is how the bottom half of the diamond with the painted girdle becomes quite dark compared to the classic girdled diamond. For me, this is one of the reasons I personally prefer diamonds with classic girdles over painted ones.

Here are the idealscope and ASET images of a diamond with a painted girdle.

An example of a branded diamond that is cut this way is an Eightstar diamond. You can see how there is zero light leakage in the diamond. However, the ASET shows that the lengthened upper girdles mean that a lot of the light return on the edge of the diamond comes from the periphery.

Dug Out Girdles

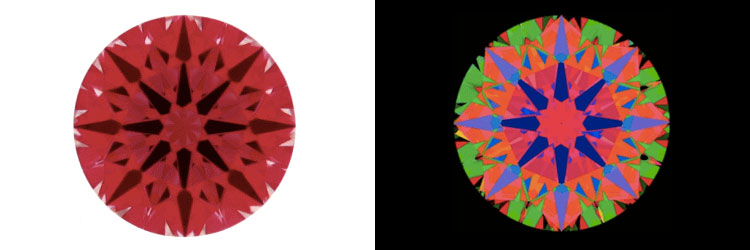

Now lets have a look to see what happens in those dug out girdles when the upper girdle angle is too steep.

Again, the left diamond is the diamond with the dug out girdle with steeper upper girdle angles. It turns out that when the upper girdles are over 44 degrees, they will begin to have unacceptable leakage under the upper girdles.

Using Good Old Gold’s diamxray technology, you can see the light leakage of a diamond with a dug out girdle very clearly.

Here are the idealscope and ASET of another diamond with a dug out girdle with upper girdle angles over 45 degrees.

As you can see, the diamxray reveals this problem better than the idealscope, however, in my opinion you don’t need the diamxray from Good Old Gold because the ASET tells the story just as clearly. The diamxray is a ‘nice-to-have’, but at the end of the day it is a redundant technology that I see as a marketing gimmick for the vendors that use them.

Classic Girdle

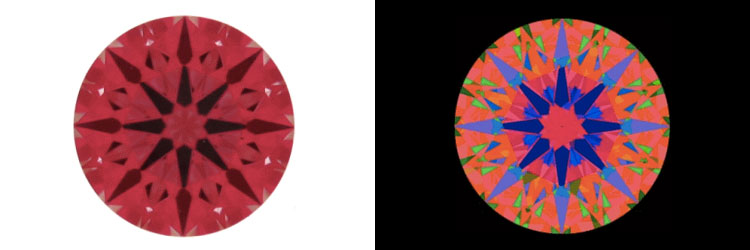

A diamond with a classic girdle will typically have upper girdle angles between 42 – 43 degrees.

I had a lot of trouble finding a diamond with an average upper girdle angle of 42 degrees. However, the diamond above has an average upper girdle angle of 42.7 degrees and the max is 43.8 degrees so you can see that most of these upper girdles are within the range that can demonstrate the kind of contrast pattern that I am talking about. You can see the effect it has on the actual diamond below.

If you find that you prefer the contrast pattern around the edge of the diamond then you should look for a diamond that shows light leakage in the upper girdle area. It will be easier to determine on the ASET. If you like this contrast pattern, then you will want to find a diamond that has an ASET that is white around the upper girdles rather than green. You will want to start by looking at diamonds that have 50% stars.

If on the other hand you want a diamond that tends more toward the painted girdle, then I call these slightly painted diamonds which have idealscope and ASET images that look like the images below.

You will find this kind of diamond common in Whiteflash’s ACA and Brian Gavin’s Signature diamonds. This is the reason why many experts in the trade will say that slight painting in some diamonds enhances the beauty of the diamond.

Conclusion

You now know all about the upper girdles and their significance and have tied this knowledge into your understanding painting and digging in a diamond. We have seen how a classic girdle can enhance contrast in the upper girdle of the diamond. We have also seen how painting in diamonds can be a good thing if it’s used to improve light return, but can also be a bad thing if it’s used for weight retention.

We have seen the negative effects of the dug-out girdle. We have also seen how a slightly painted girdle can strike a good balance between contrast and light return. You have seen examples of the idealscope, ASET, diamxray, and actual images of all of the types of upper girdle indexing. If you still have questions about the upper girdles, or if you just want some help in your diamond search, remember that you can always get in touch and I will do my best to help you out.