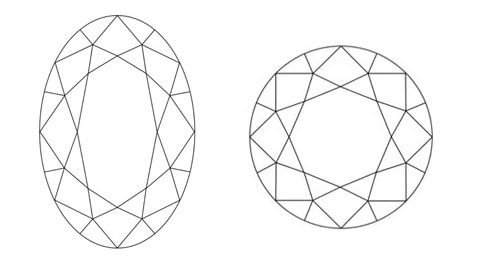

Oval vs Round

The oval’s elongated shape means that the angles at the belly of the oval are steeper than at the ends of the stone. Because of this, it is impossible to optimize the light performance across the entire oval. The result is that the light performance of an oval brilliant cut diamond cannot compare to that of a round brilliant cut diamond.

In terms of rough yield, oval diamonds are only cut from rough that is particularly suitable for cutting an oval brilliant rather than a round. In a fancy shape stone, the primary consideration is the size of the finished stone and this will impact decisions as to how high the shoulders of the oval will be. This means the rough yield is usually higher for an oval than for a round and so the price per carat of an oval brilliant is typically less than a round brilliant but more expensive than a princess cut.

For the same carat weight, is an oval larger than a round?

Let’s look at whether the footprint of an oval is larger than the round.

A 1ct oval (ellipse) with a length to width ratio of 1.4 and 61% depth will have dimensions of 8mm x 5.7mm and the typical dimensions of an ideal-cut 1ct round is 6.5mm x 6.5mm.

The surface area of an oval (ellipse) = π x r1 x r2 => 3.14 x 4mm x 2.85mm = 35.8mm2

The surface area of a round = π x r2 => 3.14 x 3.252 = 33.2mm2

This means that a perfect oval brilliant cut diamond has about an 8% larger surface area than a round brilliant of the same carat weight.

From a perception point of view, an oval looks larger on a finger than a round because there is a bigger length difference between an oval and a round than there is a width difference. An oval also looks larger from an angle because it takes on the look of a very large round at the same angle. The only problem is that most ovals are not perfect ellipses and most are cut deeper than 61% so that they actually look much smaller than a round with a similar carat weight.

Types of Ovals

Traditionally the facet arrangement of the oval brilliant cut diamond is the same as the round brilliant with 58 facets including the culet. On some certificates, you may also find that an oval cut diamond is referred to as an oval modified brilliant. This is a usually a non-issue because technically, any modification to the standard round brilliant can be considered as a modified brilliant.

In practice you will find that the terms oval brilliant cut and oval modified brilliant cut are used interchangeably. However, if the certificate states specifically that the diamond is an oval brilliant, you will know for sure that there have been no modifications made to the facet arrangement such as extra facets being added to the pavilion.

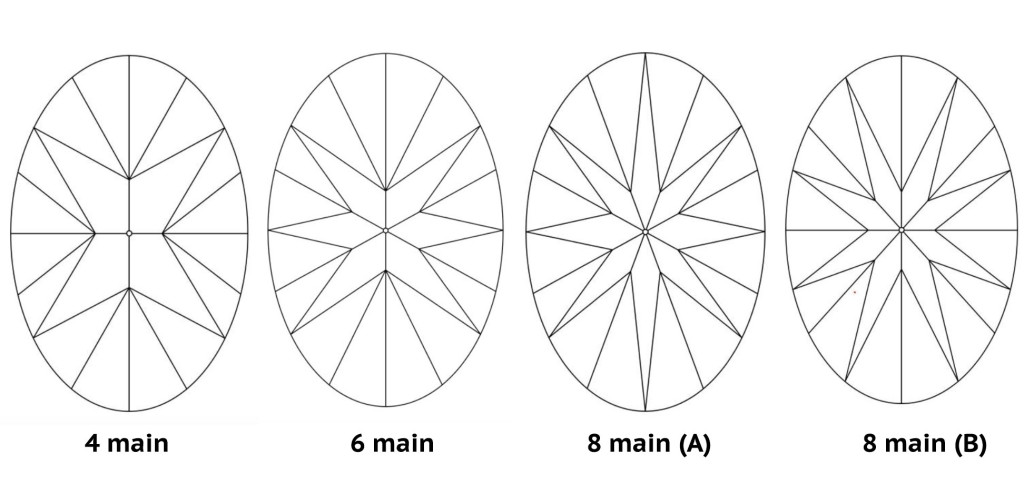

There are four standard variations of the oval brilliant cut including two 8-main variations, a 6-main variation, and also a 4-main variation. Both the 6-main and 4-main ovals only has 56-facets.

For a 6-main oval, the azimuths of the lower girdle facets at the ends of the oval have been shifted so that there are four lower girdles that are adjacent to each other on each end of the oval. In a 4-main oval, the azimuths of the lower girdles at the belly of the oval are shifted so that there are four lower girdles adjacent to each other at the ends and at the belly of the oval.

The pavilion mains of an oval are responsible for driving light performance just like in round diamonds and therefore similar concepts apply. Fewer pavilion mains means the diamond is likely to have bigger and bolder flashes of fire due to fewer but larger virtual facets. The opposite is true and you will get more but smaller pin-flashes of fire in an oval with 8 pavilion mains.

The facet arrangement will also affect the degree to which an oval will have the dreaded ‘bow tie’. The bow tie is actually made up of a combination of the virtual facets of the pavilion mains and the lower girdles at the belly of the oval. When these virtual facets turn dark because of head shadow and body obstruction, a black bow tie will be visible that can sometimes be very distracting.

A distracting bow tie is generally considered a negative because it looks like a dark inclusion that is not actually there. Although all ovals will display some kind of bow tie depending on how close you look at it, there are ways you can minimize the bow tie effect that I will be discussing later on in this tutorial.

Cut Grading

As with princess cuts and other fancies, GIA does not issue a cut grade for ovals. For a discussion on the GIA and AGS cut grading system for fancy shape diamonds, you can refer to my article on princess cuts.

The AGS light performance cut grading system applies to ovals but in reality, all the AGSL graded ovals I have ever seen have come with AGSL Diamond Quality Reports (DQR) and are not ideal-cut. This leads me to believe that currently, no one is cutting ovals to AGS ideal-cut standards.

If you’re looking for an oval with an excellent cut grade, one option is to purchase from Tiffany & Co, who has their own lab that issues gemological certificates along with a cut grade for their oval diamonds that include useful information such as the crown height, crown angle, pavilion depth, and pavilion angle. The only thing is that it seems every single oval that is sold by Tiffany & Co receives an excellent cut grade from their lab.

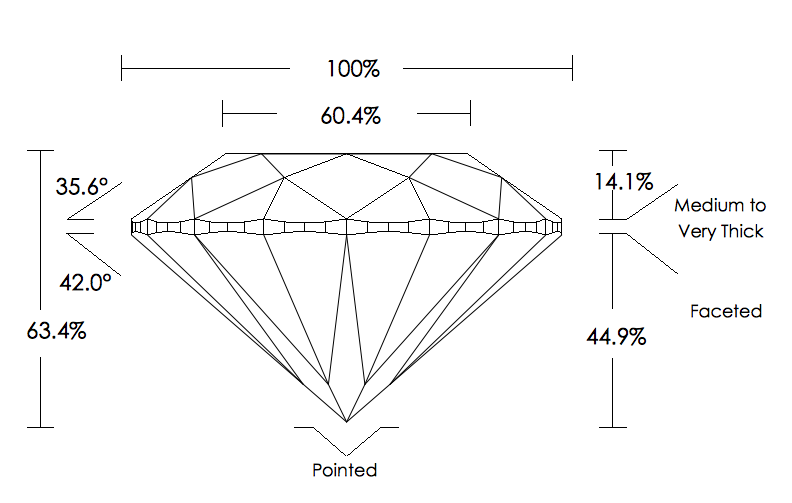

Proportions

The image above is from an AGSL DQR report and it shows how the profile view of an oval (perpendicular to the belly) looks just like a round so we can use the same terminology as for a round. You can refer to my basics tutorial on diamond cut for an explanation on the proportions of a round diamond.

What I want to point out is that the table, crown, and pavilion angles are all measured as an average of the angles across the belly of the diamond. The reason is because taking an average of all angles would produce a meaningless result. In some ways, the angles provided in an oval are actually more meaningful than those for rounds due to fewer rounding errors.

Rejection and Prediction Tools

Let me first summarize for you the basic information that is widely available online. The Accredited Gem Appraisers (AGA) published a set of cut charts for ovals in the 1980s. These cut charts were designed as a rejection tool and is generally applicable to ovals, pears, marquises, and hearts because they share similar cutting philosophy.

These charts are still available online if you search for them, but they are outdated and are not even available on the official AGA website. Nevertheless, I will show you why these charts don’t tell us enough about the cut of an oval.

The ideal-cut specifications for an oval brilliant cut diamond as published by the AGA are as follows:

Table %: 55 – 60%

Total depth: 59 – 63%

Crown height %: 12 – 15%

L/W ratio: 1.33 – 1.66

Girdle thickness: 0.4 – 4.5% or 1% – 5.5%

If you look at the numbers, they look pretty much the same as what is recommended for round diamonds. This is even more apparent when you take into account the wide-ranging girdle thicknesses that are acceptable. Essentially the charts simply tell us what does not work for a round diamond also does not work for an oval. Perhaps the only difference is that the AGA seems to be suggesting that ovals perform better with slightly shallower crowns.

Therefore, an important additional piece of information that you need about your diamond to determine the AGA cut grade is the crown height, which is not available on GIA lab reports. There is no way to determine this without measurement, so if the vendor cannot provide it the next best thing is to get an image of the diamond from the side view and try to measure the crown height off the image.

I personally agree with the AGA that what doesn’t work for a round also doesn’t work for an oval, but I don’t agree that shallower crown heights are necessarily better. Whether a shallower crown is desirable depends on how all the facets and the shape of the diamond works together and cannot simply be stated as a rule of thumb.

The problem that I have with all the AGA cut charts is that they are often over-relied upon by consumers and used for selection purposes. Even David Atlas who came up with the chart takes the position that it should be used as a rejection tool only and it merely increases the chance that you’re looking among well-cut diamonds. It is much safer and far more productive to try to understand the logic behind the numbers and I believe that this is possible without needing to become a diamond expert.

The AGA cut charts became outdated when the American Gem Society (AGS) released light performance based cutting guidelines for oval brilliant cut diamonds. Although these guidelines are also not meant for selection purposes, they are much more reliable in predicting the light performance of ovals. An interesting thing about the cut charts is that they favor a lower length to width ratio with many more potential AGS0 combinations for ovals with a length to width ratio of 1.3 than for ovals with a length to width ratio of 1.4 or 1.5.

This makes sense because a lower length to width ratio tends towards a round diamond, which will have the most number of AGS0 combinations. You should be aware that the light performance of an oval cut is judged on its own scale and therefore an AGS0 oval cannot compare to an AGS0 round. Also, a major issue of the AGS cutting guidelines is that the light performance based system is not entirely appropriate to determine oval cut grading because it doesn’t take into account of whether there are any undesirable contrast pattern effects such a distracting bow tie.

How to Pick an Oval Cut Diamond

The term oval literally means ‘egg-shaped’. At its simplest definition, an oval has a single axis of symmetry, but a well-cut oval diamond will have two axes of symmetry. A special type of oval is an ellipse, which is like a squashed round, and is defined in math as a shape with two axes of symmetry and at any point on the curve, the sum of the distances to each of the two focal points is a constant. In other words, for any given length to width ratio, an ellipse is the theoretically perfect oval without any bulge.

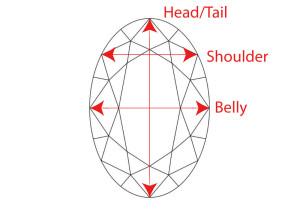

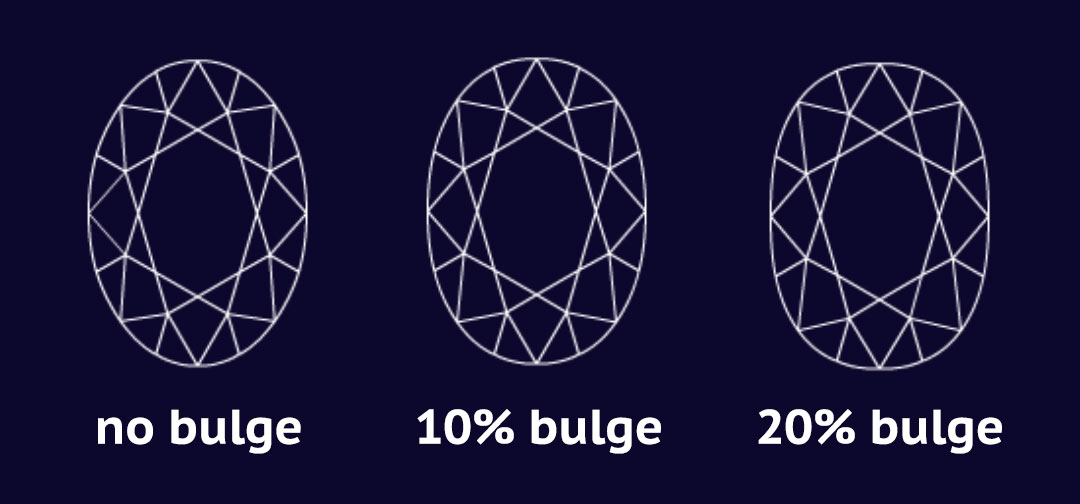

Bulge

The widest part of a perfect oval is at its belly. The degree of bulge for any oval is therefore the difference between the outline of an oval and an ellipse. A bulge means that the oval will have squarer or higher shoulders.

Although some people may have a preference for the look of a bulging oval, a bulge is seen as a form of weight retention because it adds weight without making the diamond look significantly larger. It is in the bulge that cutters can hide a lot of weight in an oval diamond.

If you take the bulge to the extreme, you will end up with a cushion shape. Here are some quick formulas to determine the ideal carat weight for an oval without a girdle.

Length(mm) x Width(mm) x Depth(mm) x 62.5/10000 x WC% (L/W ratio: 1.25)

Length(mm) x Width(mm) x Depth(mm) x 64/10000 x WC% (L/W ratio: 1.50)

Length(mm) x Width(mm) x Depth(mm) x 67/10000 x WC% (L/W ratio: 2.00)

The WC% is the weight correction percentage, which takes into account an oval’s bulge. The bulge can add up to 10% in carat weight in an oval diamond and any more I would question whether it should rightfully be called an oval.

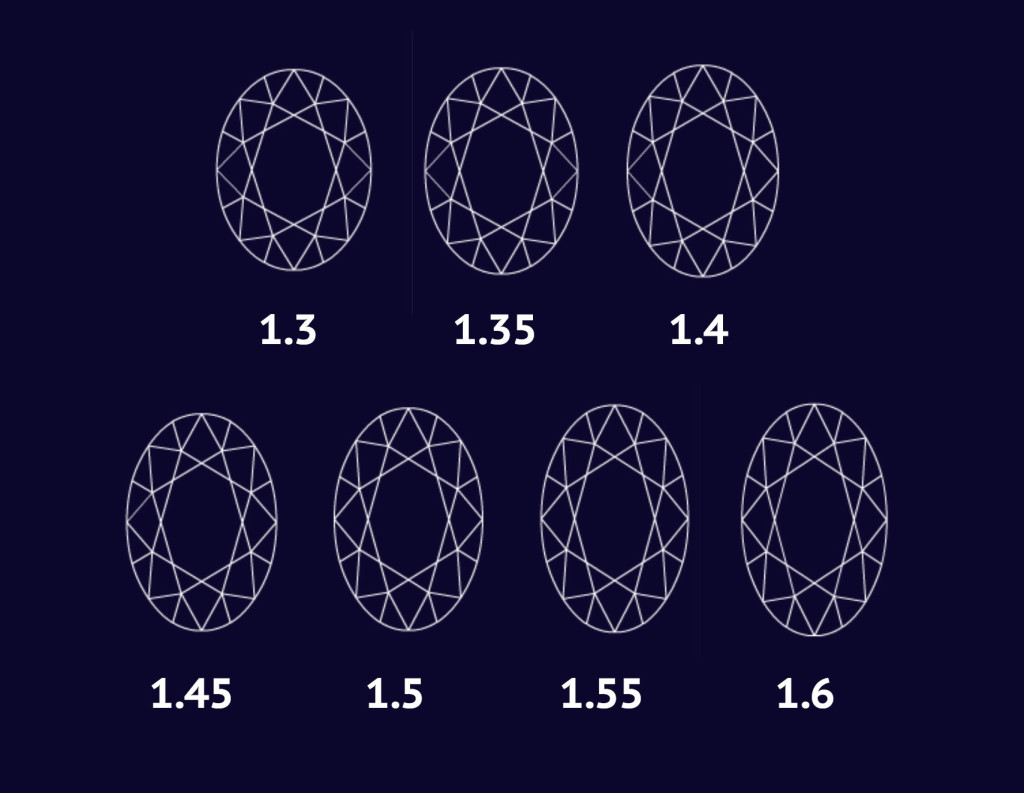

Length to Width Ratio

The length to width ratio of an oval is extremely important in defining its shape. If you increase the length to width ratio, then the oval tends toward the shape of a marquise. If you decrease the length to width ratio, then the oval tends toward the shape of a round.

It is generally accepted that ovals with a length to width ratio of 1.35 to 1.5 will have a nice oval appearance. It is still possible to find nice looking ovals with length to width ratio of 1.3 – 1.6 depending on your personal preferences. However, as with all diamond parameters, it’s often nice to strike a balance and I’ve found my personal preference for length to width ratio to be around 1.4.

What you need to be aware of is that the length to width ratio can have a significant impact on the spread of the diamond. For example, a 8mm oval with a length to width ratio of 1.25 is 1.23cts, but the same oval with a length to width ratio of 1.5 is only 0.87cts so while there is only a 1mm difference in width, the difference in carat weight is 41%.

Bow tie

The bow tie effect is one area where consumers stress over about a lot when purchasing an oval. A lot of the advice given online is that it is beneficial to minimize the appearance of the bow tie. It is possible to minimize the bow tie but it is not possible to eliminate light obstruction completely.

The trick is to ensure that the lower girdles are not displaying obstruction problems. However, because part of the bow tie is created from the virtual facet of the pavilion main, all ovals with decent symmetry will display some kind of bow tie effect and it is unavoidable.

The bow tie is analogous to the arrows in an H&A round. Now in a round diamond, the arrows are extremely important in creating structured contrast in the diamond. The arrows also give off some of the largest flashes of fire in a round diamond. The same applies to ovals, with the caveat that many ovals display bow ties that are distracting at normal viewing distances.

If you’re looking to minimize the effects of a bow tie, you may have been confused if you tried researching this topic in the past because there are conflicting opinions on how to do this. Some experts say that to minimize the bow tie you should aim for a shallower diamond, others say the effect will be less with a steeper stone. In fact, both camps are actually correct, with clarification needed.

You can minimize the bow tie with either a very shallow diamond or a very deep diamond. However, there will be trade-offs on either option. If we take the starting point that an oval has the same depth as an ideal round, then an oval will be shallower nearer to the ends. The reason is because the angles near the belly of the diamond are at its steepest.

If you cut an oval that is shallow enough to not have a visible bow tie at the belly, then the oval will be too shallow at the ends and what you will get is a flat looking stone. 6 and 4-main ovals have less of this problem because there are no pavilion facets at the ends. Lower girdle facets are steeper than pavilion facets so you get less flatness, but at the same time you lose the structured contrast pattern that the pavilion main offers.

The tricky part is that as you go shallower from the ideal depth of a round, you actually go through a range of pavilion angles where the bow tie is worse before it gets better.

This explains the confusion caused to consumers because when experts say a shallow diamond does not have a bow tie, they are referring to a very shallow diamond and not a diamond that is just a bit shallower than the ideal depth for a round. This is why the majority of ovals are actually cut slightly steeper.

As you go steeper from the ideal depth for a round, the bow tie effect gradually fades away so it is also true that a steeper diamond has less of a bow tie. The problem with having a deeper stone is that the lower girdles near the belly of the oval will have weaker light return and will eventually leak light so that a very deep oval diamond will not be very bright. The benefit of a deeper stone is that the ends of the oval will have more life to them and you can take advantage of an 8-main pavilion that gives additional contrast to the diamond.

Apart from avoiding the bow tie, the general light performance characteristics of a round diamond also apply to ovals. You can see that if you want to minimize the bow tie, you’re going to have to sacrifice some brightness in the diamond so ovals are generally not as bright as a round.

Having good symmetry is also very important if you want to minimize the bow tie effect and avoid unpredictable obstruction issues. Finally, the length to width ratio will also have an affect on the bow tie because a diamond with a lower length to width ratio will have steeper angles at the belly given the same length and depth.

Light Performance

In my opinion, consumers place too much significance over the bow tie and often forget that it’s just as important to optimize the other facets of the diamond. In my opinion, a high crown is beneficial to an oval because it plays to its strengths of having larger facets that give off bolder flashes of fire. It also means you can have a shallower pavilion so that you’re actually using the additional depth of the diamond to increase the fire of the diamond and not just to minimize the bow tie.

You can achieve this with a small table and having a total depth near the steep end stated by the AGA. When you have a thicker girdle, you want that total depth to be even deeper to ensure that you have sufficient crown height. Once you understand what to look for in a diamond, the information on the certificate becomes more meaningful.

When evaluating an oval’s light performance, it is important that you get an ASET and an idealscope. You should expect more greens in the ASET of an oval and what you’re looking for is a nice distribution of red and greens, as well as a blue bow tie that together creates a structured contrast pattern that makes for a really nice oval. The same general rules for evaluating an ASET apply and you’re looking for more reds than greens with minimal light leakage. Leakage may be black or white in an ASET depending on the type of backfield illumination used.

You will get more greens in an ASET if you aim for a deeper diamond so you should be aware that your body obstructs a lot of the light that falls on to a deep diamond so that it typically looks darker. Although it is important to get an ASET, it is also important to remember that we do not see diamonds as the ASET sees them. Our two eyes see things differently to the single lens of an ASET viewer. The angles that light arrives at each of our eyes is also different. Phenomenon such as binocular rivalry will also affect the way we perceive diamonds.

This is why even after all this analysis, you still need to visually inspect your diamond to see if it is displaying the type of effect you expect it to. It is also why although most people can see a bow tie in an oval brilliant cut diamond, the effect is nowhere near as bad as some images would suggest.

Conclusion

Picking an oval diamond is difficult because you have so many more things to consider than when purchasing a round. For me, I have to balance out my personal preference for a length to width ratio of 1.4 with the fact that a lower length to width ratio generally has better light performance.

Factoring in light performance, I would therefore aim for a length to width ratio of 1.35 and I would choose an 8-main oval with a small table. I would also do my best to minimize the bow tie. Remember that the bow tie is worst with slightly shallow diamonds and get is increasingly less noticeable as you go deeper.

It is possible to eliminate the bow tie but the trade offs are not worth it. You also have to strike a balance between avoiding a flat appearance at the ends and having light leakage at the belly as well trying to minimize the bow tie at the same time. If you really want to understand how an oval works, the best way is to download the trial version of Octonus’s Diamcalc for marquises because the fancy shapes have similar performance characteristics.