Lower Girdle Appearance

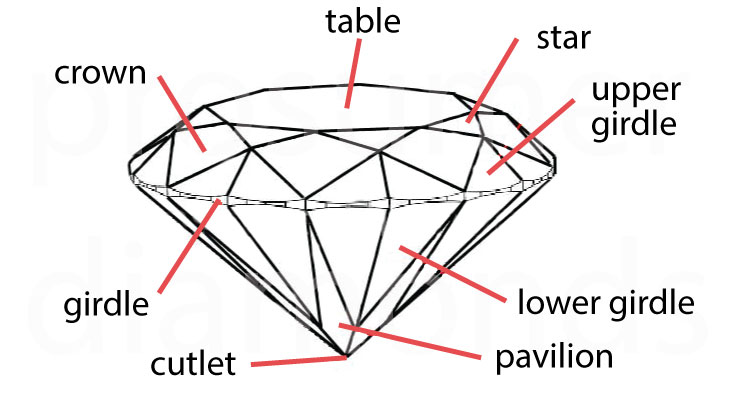

In my opinion, the lower girdles affect the face up appearance of a well-cut diamond more than any other facet. This is because the lower girdles help shape the arrows in a diamond. The arrows in a diamond is actually the reflection of the pavilion mains, the width of the arrow is determined by the two adjacent lower girdle facets with the crown facet shaping the arrow head. In general, short lower girdles cause thick arrows and vice versa.

In my How to Pick a Diamond tutorial, I gave a recommendation for a broad range of lower girdle lengths between 75% to 80%. One of the main reasons why I said this is because these are the likely numbers you are going to run into on a diamond grading certificate. It is important to remember that on these lab reports that the lower girdle length is rounded to the nearest 5%.

The Not So Minor, Minor Facet

Now despite the importance of the lower girdle facet, it has been labeled by the trade as one of the minor facets. The intentional neglecting of the lower girdles by the trade and the labs have made it easy for consumers to think that the lower girdle facets are not important. The only legitimate reason I can think of for doing this is to reduce the complexity of diamonds for consumers, but in my opinion this is confusing if not misleading.

To add to this, the trade has created two different conventions for measuring the lower girdle facet. In GIA and AGS reports, the lower girdles are measured using their length but in AGSL research material and Diamcalc, the lower girdles are measured using their height. To avoid further confusion, I want to make it clear that whenever I refer to lower girdle percentages in this tutorial, I am referring to the lower girdle length since it is the more common and familiar term you will encounter in a lab report. You can think of the lower girdle percentage as how far the lower girdle extends down the pavilion mains from a profile view.

Perhaps the real reason behind why the lower girdle facets are called minor facets is due to the way they’re cut. The lower girdles and all the other minor facets are formed in a process known as ‘brilianteering’, which is done to the diamond after the ‘blocking’ process when the major facets are formed. Another reason why the lower girdle facets could be deemed minor is because of the degree to which it can have variation yet not affect the general beauty of the diamond. Depending of your personal preferences, there is a much wider range of lower girdle percentages that work compared to crown, pavilion, and table facets.

Why does GIA rounds the lower girdle percentage to the nearest 5%? Let’s take a look at the numbers.

If you look at an AGS lab report, the lower girdle lengths are reported as accurate to the nearest percent. But as a measurement of length, we know that the typical margin of error of on optical measuring equipment is +/- 0.02mm. So if we are talking about 6.5mm 1ct diamonds, a margin of error of 0.6% of the diameter is introduced every time length is measured. Now when percentages are reported, two measurements of length are required and this means a doubling of the margin of error to 1.2% for 1 ct diamonds. In a 0.25ct diamond, the margin of error can be up to 2%. For example, if it says 77% on an AGS report, the actual measurements of the lower girdles can be anything between 75% to 79%.

Hopefully you can see that there’s not much difference between what AGS tells you and what GIA tells you. GIA simply tells you that the lower girdles are closer to 75% or 80%. In the example above, GIA would report the number as 75% and move on. This problem occurs on all the percentages being reported, but the percentages of the major facets can be verified visually so they can be reported more accurately.

The way the proportions are reported in a GIA lab report remains the same for any round brilliant diamond regardless of size so we are left with an unacceptably wide margin of error for larger stones. It seems that at least for larger stones, the accuracy provided on the AGS reports are superior to GIA. Even for smaller stones, I still prefer the AGS reporting system because it provides more practical information and I can usually tell if something is not right.

Hearts and Arrows Patterning

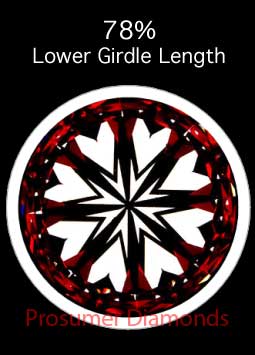

So why would we want to know the exact numbers? Well it certainly isn’t because a diamond with 75% lower girdle length is more beautiful than a diamond with 80% lower girdle length. The reason is because it’s useful for determining whether a diamond has more potential to have a good hearts and arrows image. The lower girdle length of a true H&A should be around 77-78%.

One of the problems with the way GIA reports the lower girldes is that a 77% would be rounded down to 75% and a 78% would be rounded up to 80%. It’s less meaningful because either range of lower girdles could produce true H&As. A much bigger problem is that you will not know with the certificate alone whether that 80% is actually an 82% nor if a 75% is actually a 73%.

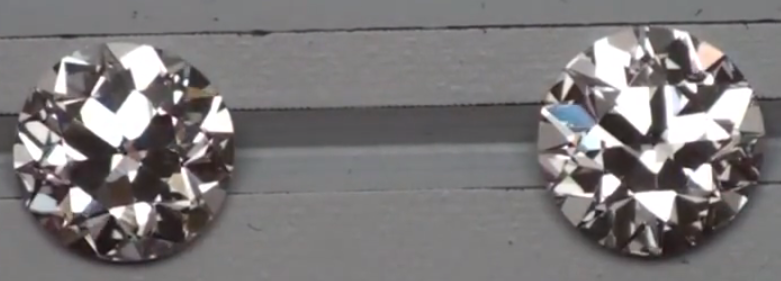

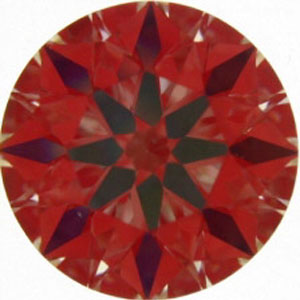

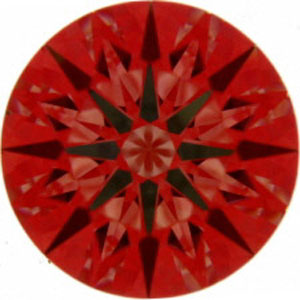

There is a huge visual difference between 75, 80, and 85% lower girdle percentages. But for a diamond with 78% lower girdle percentage, the appearance is much closer to what a 75% looks like and so I would not be confident in determining whether the lower girdles looks like a 75% or a 80% on the certificate just by observation. The only thing I can be confident from looking at the above image is that the 78% is definitely not going to be 85% on the certificate and similarly the 82% is definitely not going to say 75%.

So how can you tell?

The best way is to look at a hearts image if you have access to one. The closer the hearts are to the V’s, the shorter the lower girdles. In a diamond with a 75% lower girdle, the heart is almost touching the V and with 80% lower girdles or longer, there will be a clear cleft between the hearts. But often we don’t have access to a hearts image so it becomes a bit more complicated.

(The above images are courtesy of James Allen, used with permission.)

In most cases we do have an actual picture of the diamond so lets take a close look at these two images. I want you to only focus on the hotspots in between the arrows near the base of the shaft. If you have access to an idealscope or diamxray image, the hotspots will appear as black spots.

(This image is courtesy of Good Old Gold, used with permission.)

In general, longer lower girdles will produce increasingly larger hotspots around the base of the arrow shaft. But it is important to know that the lower girdles work together with the star facets in order to produce these hotspots. The hotspots also get larger with increasing star length.

This is also true of the pairs of triangular hotspots right under star facets.

(The above images are courtesy of Good Old Gold, used with permission.)

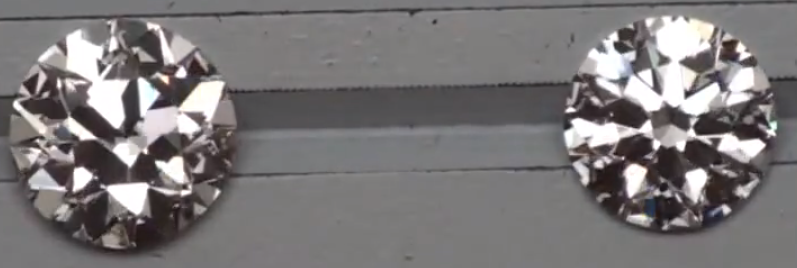

Both of the diamonds above have 55% stars on their certificate. You can see how when taken to the extremes, the shorter lower girdles of the diamond on the left makes all of the hotspots go away. Less hotspots mean less overall fire and scintillation, but the thicker arrows give off bolder flashes.

If you fix the star length, the variation in the hotspots are primarily driven by variation in the lower girdles. This means you can’t compare the hotspots of two different diamonds with different star lengths and make an accurate comment about their lower girdles. What we can do is to make an educated guess about the lower girdle length by first finding out the star length of the diamond from the lab report.

Let me explain with two examples.

Example 1:

If the star length is 50%, then you would expect smaller hotspots. So if you find a diamond (A) with 50% star length with longer hotspots and the certificate says that the lower girdles are 80%, but it doesn’t look quite like the 85% lower girdle lengths, then it seems like you are closer to 82%.

Example 2:

If the star length is 55%, you would expect longer hotspots. So if you find another diamond (B) with 55% star length with hotspots that look the same as diamond A, but it doesn’t look quite like 75% lower girdles, then you would be able to judge that the lower girdles are probably right about 80%.

I apologise if that’s confusing so if it is, please let me know and I will try to clarify things for you with more examples.

Problematic Lower Girdles

Here are two more examples of the potential problems that you may run into if you neglect lower girdles.

(The above images are courtesy of James Allen, used with permission.)

The diamond on the left is is a GIA excellent cut 1 ct DIF. On the GIA lab report, this diamond shows a lower girdle percentage of 80% with 60% stars. This is the result of a deadly combination of long lower girdles coupled with long star facets. Can you imagine how this looks like in an idealscope?

Not only does this produce a poor contrast pattern, these hotspots reflect head and body shadow and this diamond will take on a dark appearance even without light leakage. This diamond gets a GIA triple ex but to me it is totally unacceptable.

The diamond on the right is a GIA good cut 1 ct IVS2 and has 80% lower girdles and 50% stars, however the much larger table and shallower pavilion (62% and 40.2 degrees) take this concept to the extreme producing the nail-head phenomena that I’ve discussed in previous tutorials. With the way lower girdles are cut, they are never shallower than the pavilion; but the longer the lower girdles are, the shallower they become. Shallow pavilions lead to excessive obstruction and the long lower girdles exacerbate the problem. The point here is that once you begin to leave the realms of ideal cut, the combination of poor proportions work together to quickly destroy the beauty of a diamond.

Contrast Pattern

Apart from affecting hearts and arrows pattern, the lower girdles also affect the contrast pattern of the diamond. Please remember that in pictures, the black/white contrast pattern is only due to the camera lens being black, in real life these arrows will take on the color of whatever is directly above it.

The following examples are meant to help you decide what kind of contrast pattern you prefer, all of these diamonds are similar with varying lower girdle lengths:

(The following sets of images are reproduced from a very informative video on the lower half facets by Good Old Gold that you can watch here, the images are used with permission.)

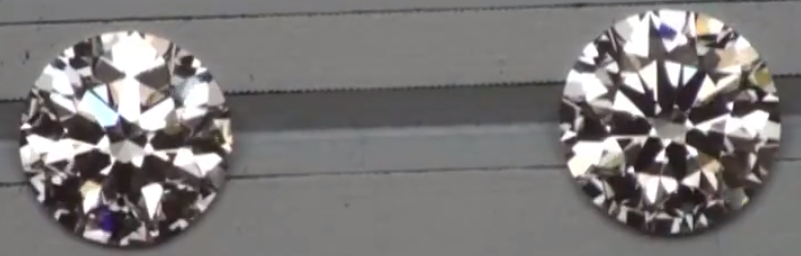

56 v 58%

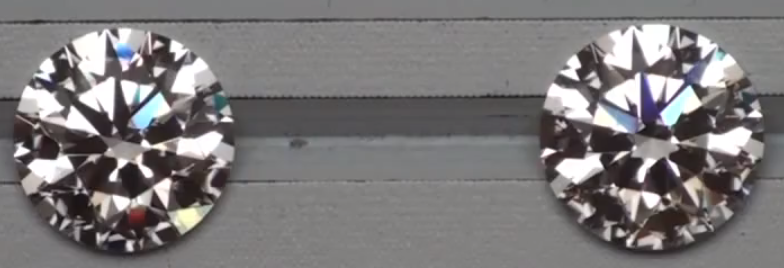

65 v 73%

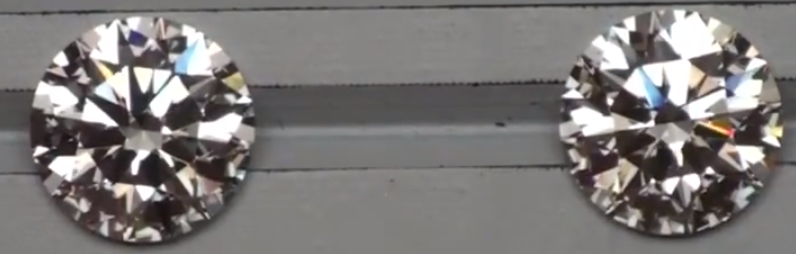

73 v 75%

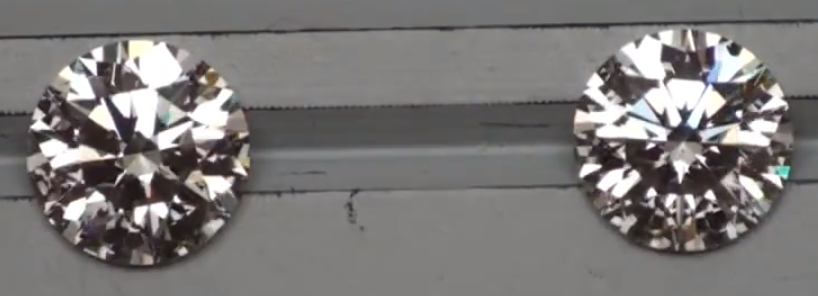

75 v 77%

77 v 80%

80 v 85%

Light Performance

Although it is good to know the dangers and what to avoid, the reality is that most of us will not be purchasing a diamond with 60% stars with long lower girdles. What is of more immediate relevance is how the lower girdles affect the character of a diamond in terms of its light performance.

The general idea is that longer lower girdles that produce thinner arrows will make the diamond sparkle with more but smaller flashes- what is known as pin-fire flash. Conversely shorter lower girdles will produce less but bolder flashes of light. There are some designer cuts that take advantage of the lower girdle facet’s ability to change the appearance of the diamond. The Leo and Solasfera brands come to mind as having 85% lower girdles and above.

(This image is courtesy of Good Old Gold, used with permission.)

These diamonds will be designed with shorter star facets so that they don’t run into the obstruction problems as explained earlier. They are also marketed for how much ‘brighter’ (because of less obstruction) and more sparkle (because of more pin-fire flash) they are than normal diamonds. But scintillation is subjective so whether long lower girdles is a good thing depends on your preferences. Also, a GIA study has shown that the 57-facet round brilliant is actually brighter than round diamonds with more facets.

If your preference is for pin-fire flash, then you should really check out the Solasfera diamond. I would also encourage you to look into fancy cut diamonds; and I particularly love the look of the Solasfera princess cuts. On the other-hand you can check out the Old European Cut or the August Vintage Cushion from Good Old Gold if you prefer bolder chunkier flashes.

Conclusion

The lower girdles affect the appearance of the diamond by its H&A pattern, its contrast pattern, and its light performance. Longer lower girdles produce thinner arrows and have more pin-fire flash. They can make the diamond look brighter when coupled with shorter star facets. Shorter lower girdles produce thicker arrows and bolder flashes. The lower girdles and the star facets can be combined to optimise for bold or pin-fire flash.