It was important for me to set up with the previous tutorials so that this tutorial will make more sense and be meaningful. I will be discussing various ways to try to identify a fair price that you should pay for a diamond. This tutorial is not designed to make you a diamond appraiser, it is designed to allow you to identify from a selection of diamonds, which diamond represents the best value for money.

Rapaport Price List

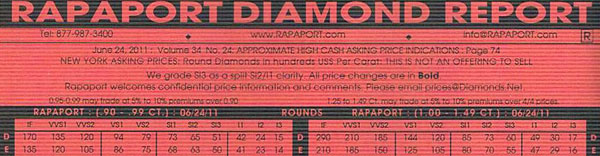

In the industry, almost every diamond dealer whether a buyer or seller negotiates based on the Rapaport price list or ‘Rap’. The purpose of this list is to provide a benchmark to enable negotiations. The benchmark is what is known as a ‘High Cash Asking Price’, which I interpret as what a ‘high’ retail price for that diamond could be. It is comparable to the market suggested retail price (MSRP) that almost everyone in the world knows is not what you actually pay for your goods.

The point is that you should not be fooled into thinking that this is a price list for diamonds that a consumer can rely on. Dealers negotiate off of a discount against the Rap because it helps them communicate better with each other. This discount is usually somewhere between 20 – 40% off of the Rap price. You will hear dealers say “twenty back” to indicate a 20% discount off of Rap. On the other hand, it is not uncommon for branded-diamonds to be sold at retail above Rap prices.

Diamond retailers also use Rap to adjust their prices to reflect current market prices. Think about it, it just makes sense when you are dealing with thousands of stones that you organise them against a reference price rather than setting each diamond’s price individually because then all the prices change together if you set each diamond’s price as Rap +/- X%. There is a chicken and egg problem here and it is often wondered whether Rap sets the prices for diamonds or if Rap is reporting the prices of diamonds. In reality it is both and it is just a continuous process, nevertheless Rap is very important to the diamond industry.

Is it feasible to work off of Rap to find a price that is justified?

The Rapaport price list takes into account 3 out of the 4 C’s namely color, clarity, and carat. What it doesn’t take into account is the cut, symmetry, polish, and fluorescence to say the least. Dealers will have access to much more information than what is simply on the list to find out how much discount should be applied for diamonds with different characteristics. This is why in my opinion, using the Rapaport price list can be more dangerous than helpful for a consumer. But this is not to say that Rap is never useful. I have actually found the price list very useful to find a fair price difference for comparable stones that have different color, clarity, or carat.

The copyright of the Rap price list is very well protected and you simply will not find it available online. Your first option is to purchase the latest copy of Rap and you get a one-week subscription for US$50. Alternatively, what you could do is ask a vendor if they can show it to you but they are unlikely to reveal that information to you let alone provide you with a copy.

(Edit: A big Thank You! to all the awesome readers who have have supported this site, Prosumer Diamonds now has access to RAPnet, which includes access to wholesale diamond prices, the monthly price lists + price calculator + trade screen, and other awesome stuff that I can use to help you out in your diamond search.

If you want access to diamond prices, the best thing to do is to contact me, and although I too will not reveal exactly what is on the list, I will go one step further and explain to you whether or not a diamond is good value for money and I’ll tell you why I think so.)

If you want to go down the DIY Rap route, here is a suggestion. First take a look at some outdated copies of the Rap that are all over the internet, but the newer the better. Study it, and pay attention to how it works.

Here are some of the main points:

• Make sure you are looking at the Rap for the shape you’re looking for (i.e. Rounds) – you can find this in between the table titles.

• There are four tables with four different carat ranges, make sure you’re looking at the right one.

• All the prices are in US$100s.

• Take all annotations as advisory and not rules.

What you can understand from any old Rap are where there are big price jumps. Now these price jumps, often called magic numbers, will depend on the market so the current versions will be different. But you will generally be able to get the gist of where price jumps are to be expected. More importantly, once you are familiar with how the Rap works and you have narrowed down your selection criteria, you can quickly see what the price difference is like when you ask to see a current version. When you see it, note it down for future reference.

This approach will only work if the diamonds are truly comparable and this requires Prosumer Level 3 knowledge. So the Rap isn’t as helpful as it appears to be, what else can we do?

Lab Reports

In general, diamonds with certification will have a higher premium than those that don’t. Here you should think like a dealer. The vast majority of good-looking diamonds will be sent to GIA for certification. GIA diamonds will command a higher premium than say a diamond graded by EGL, even if they are the same grade. Here is the reality. If a dealer believes a diamond is a GIA D color, there is no point in sending that diamond to EGL. Dealers only send diamonds to the lesser labs when they want a report to look nicer so that the diamond is more saleable.

The general rule is 2 color or clarity grades different for an EGL certificate so you should factor this into the price. AGS diamonds generally command the least discount off Rap, but this is not a rule. But for the majority of you readers out there this is probably not going to be a problem for you and I would be surprised if you are comparing GIA to EGL diamonds.

Certifying a diamond is also an economic decision by whoever gets it done. Apart from the obvious benefits of certification, it is done primarily to add value to the diamond and making it easier to sell. But certification costs money and for small diamonds, this can be a significant percentage of the profit margin. That is why you only see higher quality goods being certified. This is also the reason why GIA won’t include a clarity plot with diamonds that are below 1ct.

Weight ratio

Let me make a bold suggestion. Why don’t we forget about what the industry tells us about the price of a diamond and think about it from our own perspective. The weight ratio of a diamond tells us how many percent heavier it is to a reference diamond with ideal performance. We can use the weight ratio to deduce that a diamond with a 1.05 weight ratio should cost 2% less per carat than a comparable diamond with a weight ratio of 1.03. This is not often the case, but it can equally be said that if each of these diamonds had the same price per carat, then the diamond with a lower weight ratio is better value for money.

Weight retaining

Sometimes, the weight ratio is not sufficient to tell us detailed information about how a diamond retains its weight. It may have a good weight ratio but have a bit of weight saving here or there. Here is where we should think like a diamond cutter. There carat weights such as the 1ct mark that exert the greatest pressure on cutters to ensure they meet a certain category.

Here is an example. A cutter knows that a thin to medium girdle is in greater demand. He has a diamond that he can cut a thin to medium girdle but the diamond just misses the 1 ct mark, you can bet your house that he is going to try to use cutting techniques to retain that essential bit of weight. What you can do is use the knowledge you gained in Prosumer Level 2 to identify all the places where a cutter can retain weight.

This could be through making some angles slightly steeper or by slightly painting or digging the facets. You cannot expect a vendor to sell you a diamond that has been made to meet a certain price range for the price it would have been if the diamond missed the mark. But what you can do is avoid these diamonds and the best way is to avoid those diamonds that are on the border of the magic numbers. You will find that these diamonds are generally better cut. If you’re dead set on getting a 1.00ct, then you can either be prepared to lose some of that weight or spend a longer time searching.

Think about the vendor’s margins

This is an obvious one. If you’re buying from a retail store, be prepared to pay a higher price to account for higher margins that have to offset those overheads. The same thing goes for branding, you are essentially paying for the marketing costs. This applies the same to online vendors as brick and mortar stores. You should also think about whether that vendor is devoting a lot of resources into R&D, innovating new types of cuts, invests in expensive equipment that provides you with useful information, carries a lot of choice, and their reputation.

Less obvious is to try to think about the vendor’s supply chain. A vendor that has a high turnover will be able to source their diamonds, even for the same quality, cheaper because they are more important clients for their suppliers. There are not that many large suppliers out there and it is not that difficult to work out for yourself who the big players are, and who has the luxury of selecting the cream of the crop diamonds.

Factor all of this into what you think is getting value for money. If you don’t want to pay the premiums for value added services and marketing, then it makes your choice of vendor that much easier. One thing that is often neglected is after-sales care. Believe it or not it may be worth it for some people to have the pleasure of a free ring cleaning from Tiffany every time they walk past for the rest of their lives. How do you put a value on that?

Clarity

I’ve talked about clarity in the basics tutorials, but I didn’t tell you what to look for within a clarity grade. Here you should think like a diamond grader. A diamond grader considers 5 factors namely size, number, position, nature, and color. Size and number don’t need to be explained.

Position is important, as inclusions that are more visible (i.e. directly under the table) are less preferable, worse if the inclusion is a reflector that has mirror images of the inclusion all over the place. Think about whether inclusions can only be seen from the pavilion, can only be seen at certain tilt angles, can only be seen at certain focal lengths, can only be seen if light is hitting it at just the right angle, if the inclusion can be covered with a prong when set, and the durability implications of large feathers.

The durability is also covered in the nature of the defect. Apart from this, the nature of an inclusion is not that important for our discussion here, as it simply categories the type of defect as an internal inclusion or external blemish.

Color is important and is also judged as ‘relief’, which refers to the contrast between the defect and the diamond, and again this is about visibility. Colorless inclusions are better than white are better than dark. An interesting exception to this is that a single black pin-point may be preferable to a white pin-point because it is harder to see.

Color

In my basics tutorial on diamond color, I told you that each color grade is actually separated into high, medium, and low. First you can get a GIA graded diamond for a better chance of the diamond to be graded the correct color, but you can do better than that. There are online vendors out there that provide you with 360-degree views of the diamond and I have shown you that you can use this to effectively compare color.

I’ve done this exercise myself and have been able to pick out very clearly 3 color distinctions within each grade from D to K so you should be able to as well for your color range. Doing this, you can even find a high H-color diamond that is an even better color than a low G-color diamond for example.

If you have several loose diamonds of the same color grade in front of you, you can try to grade these diamonds yourself using the same techniques as the grader. Have the diamonds table-down, in a line and on a folded sheet of plain white paper. If the stone is the correct grade, then the diamond on the left should appear darker than the stone on the right. Re-arrange the diamonds and choose the diamond with the lightest color. If it is available to you and you feel up to the challenge, choosing a high color is a great way to ensure that you have excellent value for money.

Conclusion

The key takeaways in this tutorial are that you should be careful when using the Rapaport price list. There is no point in trying to ‘game’ the Rap Sheet so if you use it, use it to identify the current price difference between comparable diamonds in terms of the color, clarity, and carat. Beyond that, you can use the weight ratio and weight retaining knowledge to help identify those diamonds that have the best value for money.

I have also talked about the different ways you can ensure you have the best color and clarity diamond within the range that you selected. But here is one last piece of advice, and that is – preferences first. Find a diamond with the characteristics that you prefer, that should be your priority and then once you find several potentials, use these methods to identify which is your perfect diamond.

(Edit: I have written an article on understanding on how to price a diamond using the Rapaport price list here. It’s worth checking out if you’re looking to understand more of the frequently asked questions regarding pricing)